(first appeared on Loch raven Review in 2012)

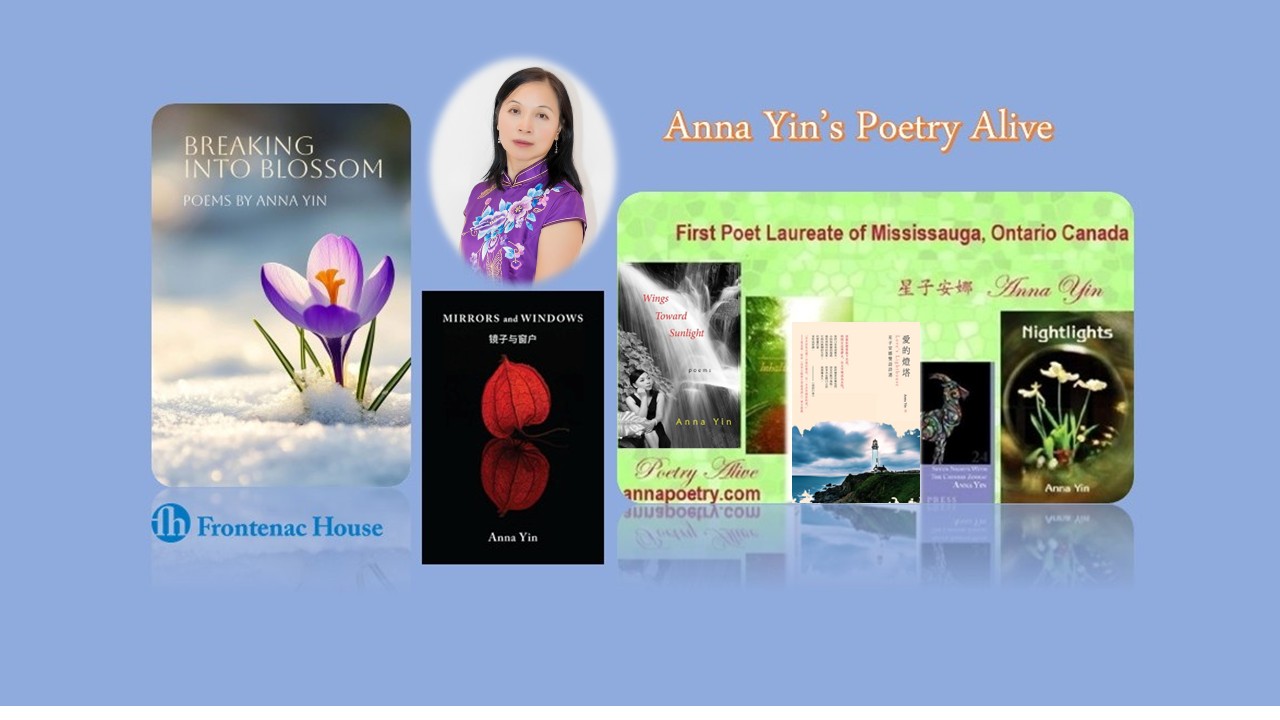

Wings Toward Sunlight

by Anna Yin

Mosaic Bress

ISBN: 0-88962-928-8

Review by Lois P. Jones

Wings toward Sunlight, Anna Yin’s first full length collection of poetry begins with a little known quote from Emily Dickinson: “the soul should always stand ajar, ready to welcome the ecstatic experience.” This invitation is both an evocation and incantation. For to read the poetry of Ana Yin is to court the landscape of ecstasy. Not the Sufi-bound realms of Rumi’s rapture but a quiet jubilance. So quiet and yet so immediate that I was taken beyond a book of poetry to the living world of creation. It is a way to “be”, to watch nature, a vase of flowers dying with the same wonder one regards the Milky Way on a clear and endless summer night. A kind of reverence for the moment. This is the deep listening that brings to mind poets like Rainer Maria Rilke or Lee Young-Li, using nature as a guide toward stillness. Anna Yin’s stillness is one where time is not part of its alchemy. There is a classic, masterful touch, an underlying Taoist’s inscription. Yet Wings still manages to take us into its contemporary trajectory, mixing philosophy with modern circumstance.

The book opens with one of my favorite works of the collection. Here, we enter a Basho-like world where rain transfixes as it nurtures and reminds us that water, like spirit is a sentient thing, engaging what it touches and touching what is engaged until the reader too, at poem’s end, is renewed.

Rain

You don’t pray for rain in mountains.

It comes and goes as if to home–

sometimes wandering in clouds,

other times running into rising streams.

The soil is forever soft.

Leaves unfold to hold each drop.

At the end of each cycle,

you always hear it singing

all the way home—

kissing leaves,

tapping trees.

Some drops stay longer on tall branches.

All of a sudden, a wind blows;

they let go—

a light shower

surprises you

sitting motionless under a phoenix tree.

Later in the poem Rainy Night, rain takes on a sensual, prophetic nature:

Roses on the sills bloom—

like an earlier agreement

between a man leaning by the window

and a facing mirror…

Here we begin to feel a sense of the other, the shadow lover, real or imagined whose presence courses through the collection. The “you” is a ghostly figure, oblique at times, incandescent in others. He appears and disappears as the poet takes us through a kind of word-hewn twilight where orchid nights and moonlit reflections create an exoticism. I feel at moments a voyeur holding my breath before a spell – the birth of a secret universe that is intoxicating and nascent.

I have always had an affinity for work by non-English language poets. Like Bly, I am a fan of foreign poets who write a poetry very different from the poetry written in America. Ana’s voice offers the richness of two worlds – Asia and the western world which meet in the mist somewhere between reality and imagination, between contemporary sensibilities and Eastern languor. Looking into The Door we see:

The moon – a birth book,

faces change, pages turn.

Concepts that leap from image to symbol, taking simple words and turning them into sophisticated layers of contemplation. In these few words the lunar cycle invites more than a singular event – it’s a metaphysical passing from one life to another. Perhaps the poet did not intend this but that’s part of the power of this collection. We become the page itself following as the “wild lilies cling to faded fences” and “from an unknown bird, a few feathers drop, then rise again.”

In Snake, the poet confesses to an unknown sin that slithers throughout the text asking the reader to examine his own transgressions and perhaps release them in the process. And wouldn’t it be easy to leave our darkest thoughts just here:

when I left, it was dark,

and I waded through a river

where a black rose floated.

Tension and release, shadow and foreshadow, the lyric language and furtive conceits embrace the reader in an almost sacred way. So many of the poems touch on longing but not in a sentimental, clutching fashion but in the tradition of Wang Wei’s “Magnolia Slope,” where loss is represented not through a lover’s spat but as tea grown cold:

The afternoon tea grows cold;

its color, like our sunglasses, turns dark.

On the surface, our reflections blur.

The ferry boat moves into open water.

My fingers play on the cold cup.

Wind catches my hair and sends it flying;

your rising hand hesitates to touch.

Somewhere between us,

your eyes meet mine—

You light a cigarette, inhale.

The clouds spread.

We watch

birds flying elsewhere.

In one of the best surprises of the book After Reading Ted Hughes’ Full Moon and Little Frieda” the poet is unafraid to call down the moon — the tired moon that academics warn against and in whose shadow peevish journals squirm. Here Anna Yin dances to her own rivered tune. Watching the small village become a floating island where among rows of windows, the night flows, and I’m wide awake. At the end she commands Moon, lift your bucket, come out once more. I won’t make a sound. And we, silent readers tread softly through the pale landscape and gladly await its ascent.